Empowering your victims: Why repressive regimes allow individual petitions in international organizations

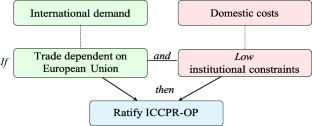

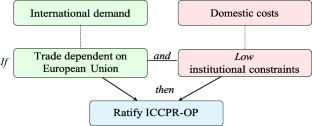

The growing literature explaining why repressive regimes ratify human rights treaties fails to explain why some regimes take the additional step to delegate authority to their people to file international legal complaints while others do not. I examine individual petition mechanisms in the United Nations which allow individuals to file complaints to an overseeing treaty body. I argue that repressive regimes face international incentives to signal their commitment to the European Union, a global power with a strong and continued interest in the global human rights regime. Repressive regimes, however, only ratify agreements when they perceive low domestic costs with little institutional constraints on the executive. In support of my theory, I find that repressive regimes are more likely to ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’ Optional Protocol allowing individual petitions when they are trade dependent on the EU while facing lesser institutional constraints, both legislative and judicial. The results are similar to explaining treaty ratification, but the interaction is substantively larger for OP ratification among repressive countries, highlighting the increased costs repressive leaders face to allowing individual petitions. Individual standing in the overseeing body of the ICCPR is one example of non-state actor access in international institutions, which is an important component of understanding institutional design and compliance.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save

Springer+ Basic

€32.70 /Month

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Buy Now

Price includes VAT (France)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Similar content being viewed by others

Empowering to constrain: Procedural checks in international organizations

Article 20 April 2024

The (D)evolution of a Norm: R2P, the Bosnia Generation and Humanitarian Intervention in Libya

Chapter © 2013

Three Generations of International Human Rights Governance

Chapter © 2017

Data availability

The dsataset analyzed for the current study with corresponding code is available at the Review of International Organizations' webpage.

Notes

See Conrad (2014); Hollyer and Rosendorff (2011); Vreeland (2008).

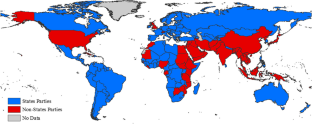

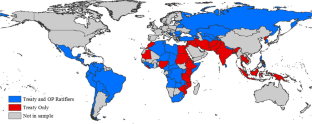

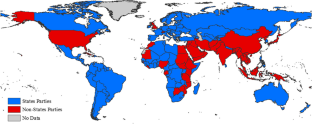

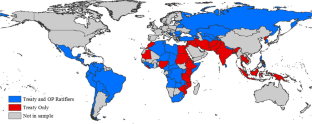

Only 18 countries are neither States Parties nor signatories to the ICCPR. Out of 173 States Parties to the ICCPR, 117 are States Parties to the ICCPR-OP.

Physical integrity violations include torture, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, political imprisonment, genocide, and mass killings.

I measure repression at the time of OP ratification, and if a government did not ratify the OP, I measure repression at the time of ICCPR ratification.

I purposefully use the term “individual” or “person” rather than “citizen” because nationality is irrelevant when filing a petition in the Human Rights Committee. Jurisdiction is based on government action, regardless of nationality or residence.

As of writing, eight of the nine human rights treaty bodies may, under certain conditions, receive and consider individual complaints or communications from individuals. The petition mechanism has not yet entered force for the Committee on Migrant Workers.

This work has a restricted geographic and treaty scope: focusing on transitioning countries in Central Asia and Central and Eastern Europe and four main treaties.

Norms and culture play a role in international politics but are not the focus of this paper, which seeks to explain this empirical puzzle from a rationalist perspective. An early work examining commitments to the international covenants– both treaties and their OPs– Cole (2005) finds support for rationalist and world polity institutionalist theoretical perspectives over the clash of the civilization thesis. For example, norms can be included in leaders’ cost/benefit analysis. Unlike ratification of some human rights treaties, allowing individual petitions is not a widespread or salient norm.

The United States supports human rights around the world but is quite skeptical of and opposed to international legal enforcement. The US has not accepted any individual petition mechanisms and has been outspoken against the International Criminal Court. As a placebo check, I include US trade (Barbieri & Keshk, 2016; Barbieri et al., 2009) and aid (Tierney et al., 2011) dependence. Appendix Table 1 and Figure 1 show that the key results do not hold for US dependence. Economic dependence on the US does not increase the probability a country ratifies the ICCPR-OP.

The European Union did not exist as a political entity for the entire sample of interest, starting when the ICCPR was open for ratification in 1966. I use “European Union” as shorthand to discuss not only the regional organization but also its constituent countries before and throughout the regional integration process.

The European Union is the most powerful global actor that fits this theory. This theory also applies to Canada and Australia. This paper focuses on the EU given its broader pattern of global trade.

Members of the Council of Europe were not all among the early ratifiers of the ICCPR-OP (membership has greatly expanded over time), but this is likely due to their strong, pre-existing regional institutions, presenting little pressing need.

European Union News. 18 April 2017.

European Union News. 7 October 2016.

European Union News. 19 September 2016.

“UN: European Union’s View on Human Rights Situation in Various States Contested in Third Committee.” M2 PRESSWIRE. 14 November 1997.

See Goodman and Jinks (2004); Simmons and Elkins (2004) for relevant discussion of policy diffusion.

Donno and Neureiter (2018) finds human rights clauses in EU agreements are conditionally effective: clauses are associated with improved political freedom and physical integrity rights, but only in countries that are more heavily dependent on EU aid (suggesting economic leverage is more important than a country’s strategic importance).

No countries in this repressive sample have ratified and subsequently withdrawn. While rare, countries can reconsider this commitment: Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, neither considered repressive countries by this study’s operationalization, both denounced the Optional Protocol after ratification. Belarus is analyzed here and denounced the ICCPR-OP in 2022, stating the denunciation would take effect three months later, in February 2023. These actions are after the end of the temporal sample.

Numbers as of February 2021. The latest update of petitions is from March 2016 according to the UN website.

I restrict the sample using values below the mean (Appendix Table 2 and Figure 2) or negative values (Appendix Table 3 and Figure 3).

I opt for a Cox model because its semi-parametric nature has fewer distributional assumptions than parametric models. The Cox model has one core assumption: the proportional hazards assumption. For each model, I test for a violation of the PH assumption by estimating, examining, and plotting the scaled Schoenfeld residuals. As expected, p-values are not statistically significant at standard significance levels for any variables. The global p-values for Models 5 through 8 respectively are 0.67, 0.72, 0.67, 0.75, which provides strong evidence that the PH assumption is not violated. I also run a logistic regression with cubic time dichotomous variables as detailed in Carter and Signorino (2010). The results from this model are shown in Appendix Table 4, and the marginal effects plots are included in Figure 4 using Hainmueller et al. (2019). The key results are robust to this model specification.

The European Union was not a political entity for the entire temporal sample. The IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics covers 29 countries for all periods. Of these European countries, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, and Romania are in my repressive sample. The results are robust to excluding these four countries.

All economic data are adjusted to constant 2012 USD.

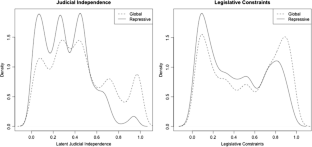

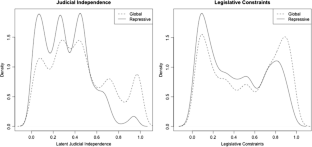

I use the update of Linzer and Staton’s (2015) Latent Judicial Independence, covering 1900–2015 which incorporates newer versions of its original, component indicators and adds measures from the Varieties of Democracy (V-DEM) project, specifically high court independence and high court compliance.

This index is formed by taking the point estimates from a Bayesian factor analysis model of the V-DEM indicators for legislature questions officials in practice, executive oversight, legislature investigates in practice, and legislature opposition parties.

The correlation coefficient between respect for physical integrity rights and judicial independence is 0.339, and between rights and legislative constraints 0.236.

It is important to note that for judicial independence, extremely low values are not meaningfully different. This is not a problem in the present analysis given the variation in the sample of interest. This, however, becomes a problem when I decrease the sample for robustness, decreasing the variation in judicial independence, which leaves mostly low values. This is discussed with the robustness checks.

For robustness, I include additional controls not presented here: financial crises (Smith-Cannoy, 2012), executive job security (Conrad & Ritter, 2019), and British legal system/common law (Simmons, 2009a). Appendix Table 5 includes financial crises, and Table 6 includes legal system type. Following Conrad and Ritter (2019); Young (2012); Cheibub (1998), I create a measure of executive job security using predicted values from a hazards model. I substitute this insecurity measure for my domestic institution variables, displayed in Appendix Table 7.

Adding the popular measure of democracy Polity2 is problematic given one of its component variables is constraints on the executive. I use the “core civil society index” from V-DEM which asks, “How robust is civil society?” where a robust civil society “enjoys autonomy from the state and in which citizens freely and actively pursue their political and civic goals, however conceived” (Coppedge et al., 2021; Pemstein et al., 2021). The results are robust to using these component variables instead: civil society organization (CSO) entry and exit, CSO repression, and CSO participatory environment. As a robustness check, I substitute (given the very high correlation between these two variables), an index of electoral democracy that includes neither institutional constraints on the executive nor human rights (Coppedge et al., 2021; Pemstein et al., 2021). This, however, is highly correlated, with the institutional constraints variables. The main results hold, shown in Appendix Table 8.

I substitute two alternative indices measuring respect for physical integrity: CIRIGHTS (Cingranelli et al., 2021) and Varieties of Democracy. Higher values still represent higher respect for these rights. The results shown in Appendix Tables 10 and 11, and Figures 5 and 6 show the results are robust.

The eight core human rights treaties counted are: International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families; International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance; and Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

This is robust to total counts as well as neighbor measures (both proportion and count).

I also substitute a regional measure for a global (lagged) count of ICCPR-OP ratifications, capturing the establishment of a global norm. The results are robust, as shown in Appendix Table 13, which uses the logistic regression with cubic time variables because this variable is the same for all countries for any year, which is incorporated into the base hazard rate.

The hazard ratio is the exponentiated coefficient and is a central statistic in survival analysis. An estimated hazard ratio of one indicates no association between the covariate and the hazard (i.e. experiencing the event, here OP ratification). Values above one indicate the covariate is associated with an increased hazard, and values below one a decreased hazard. Here, I opt for the traditional coefficient (not exponential, hazard ratio) for a more intuitive presentation. In line with other regression analyses, this is centered around zero instead of one.

The percent change in the hazard is calculated by subtracting one from the exponential coefficient (hazard ratio) and multiplying by one hundred.

Appendix Table 12 and Figure 7 show the results from these models.

I note that judicial independence loses significance in some of the alternative specifications. This is not surprising given the decreased sample size. The coefficient point estimates remain similar, and the other results hold. Additionally, judicial independence is a latent variable. The data include a point estimate and a measure of uncertainty. The analysis presented in the main paper uses the point estimate, ignoring the uncertainty of the estimate. Following the method detailed in Crabtree and Fariss (2015), I incorporate this uncertainty with bootstrapped standard errors. The results in Appendix Table 9 support the core results.

Additionally, I run the core models explaining OP ratification and include the eight repressive countries that have not ratified the treaty. The results are robust to this alternative specification with the full population of repressive countries.

Given the same threshold of repressive, most countries are either repressive every year in the sample or only a few years (which is a small proportion). Only two countries are considered repressive in a notable proportion of the data: Singapore (15 repressive years out of 51) and Malaysia (36 repressive years out of 51).

I include the same control variables and adjust the regional lag variable from the prior analysis from OP to ICCPR regional ratifications. Unlike the first stage, there is evidence that the proportional hazards assumption is violated. Therefore, the models include interactions for the two variables of concern, Regional Lag and Human Rights Treaties Lag, and time (Mills, 2010). These results are robust to an alternative specification: logistic regression with cubic time variables shown in Appendix Table 14 and Figure 8.

Models 1–4 show no significant, standalone effects for either trade or aid dependence.

This index asks: “To what extent does government respect press & media freedom, the freedom of ordinary people to discuss political matters at home and in the public sphere, as well as the freedom of academic and cultural expression?”

The interaction for aid dependence is not significant. The marginal effect plots more clearly show similar results to the main findings.

There is a large, but not perfect, overlap between these two samples. Eighty countries are in both repressive and this broader sample. Eight countries drop out in this specification (that is, are considered repressive but are either in the EU or OECD): Mexico, Chile, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, Estonia, Turkey, and Israel. Here, 52 new countries are added, including Costa Rica, Ghana, Botswana, Qatar, and Laos. I note the main results of the repressive sample are robust to excluded these eight EU or OECD countries.

There is little work on the determinants of filing petitions. Cole (2006) finds that global civil society, measured by international non-governmental organizations encourages petitions, but this is notably different than a robust civil society.

Human Rights Watch’s 2000 report “Democratization and Human Rights in Turkmenistan” details these abuses and states the “catalogue of human rights abuses in Turkmenistan is extensive and well-documented, and amounts to a total lack of basic civil and political freedoms.”

References

- Ariotti, M., Dietrich, S., & Wright, J. (2022). Foreign aid and judicial autonomy. The Review of International Organizations,17(4), 691–715. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bagashka, T. (2014). Unpacking corruption: The effect of veto players on state capture and bureaucratic corruption. Political Research Quarterly,67(1), 165–180. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barbieri, K., Keshk, O. M. G., & Pollins, B. M. (2009). Trading data. Conflict Management and Peace Science,26(5), 471–491. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barbieri, K., & Keshk, O. M. G. (2016). Correlates of war project trade data set codebook, Version 4.0. https://correlatesofwar.org

- Beckfield, J. (2008). The dual world polity: Fragmentation and integration in the network of intergovernmental organizations. Social Problems,55(3), 419–442. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Beckfield, J. (2010). The social structure of the world polity. American Journal of Sociology,115(4), 1018–1068. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Brady, D., Beckfield, J., & Zhao, W. (2007). The consequences of economic globalization for affluent democracies. Annual Review of Sociology,33(1), 313–334. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis,14(1), 63–82. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bueno de Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2007). Foreign aid and policy concessions. The Journal of Conflict Resolution,51(2), 251–284. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Byrnes, A. (2000). An effective complaints procedure in the context of international human rights law. In The UN Human Rights Treaty System in the 21 Century. Brill Nijhoff pp. 139–162.

- Carey, S. C. (2007). European aid: Human rights versus bureaucratic inertia? Journal of Peace Research,44(4), 447–464. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Carter, D. B., & Signorino, C. S. (2010). Back to the future: Modeling time dependence in binary data. Political Analysis,18, 271–292. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cheibub, J. A. (1998). Political regimes and the extractive capacity of governments. World Politics,50(3), 349–376. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chorev, N. (2012). Changing global norms through reactive diffusion: The case of intellectual property protection of AIDS drugs. American Sociological Review,77(5), 831–853. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cingranelli, D., Filippov, M., & Mark, S. (2021). The CIRIGHTS Dataset. Version 2021.01.21. The Binghamton University Human Right Institute. Google Scholar

- Cole, W. M. (2005). Sovereignty relinquished? Explaining commitment to the international human rights covenants, 1966–1999. American Sociological Review,70, 472–495. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cole, W. M. (2006). When all Else fails: International adjudication of human rights abuse claims, 1976–1999. Social Forces,84(4), 1909–1935. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cole, W. M. (2012). Institutionalizing shame: The effect of human rights committee rulings on abuse, 1981–2007. Social Science Research,41(3), 539–554. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Comstock, A. L. (2021). Committed to rights: UN human rights treaties and legal paths for commitment and compliance. Cambridge University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Comstock, A. L. (2022). Legislative veto players and human rights treaty signature timing. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 1–29.

- Conrad, C. R. (2014). Divergent incentives for dictators: Domestic institutions and (international promises not to) torture. Journal of Conflict Resolution,58(1), 34–67. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Conrad, C. R., & Ritter, E. H. (2013). Treaties, tenure, and torture: The conflicting domestic effects of international law. The Journal of Politics,75(02), 397–409. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Conrad, C. R., & Ritter, E. H. (2019). Contentious compliance: Dissent and repression under international human rights law. Oxford University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Lindberg, S. I., Skaaning, S.-E., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, S. M., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Knutsen, C. H., Krusell, J., Lührmann, A., Marquardt, K. L., McMann K., Mechkova, V., Olin, M., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., Pernes, J., Petrarca, C. S., von Römer, J., Saxer, L., Saxer, L., Seim, B., Sigman, R., Staton, J., Stepanova, N., & Wilson, S. (2017). V- Dem (Country-Year/Country-Date) Dataset V7.1. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://v-dem.net/data/dataset-archive/

- Crabtree, C. D., & Fariss, C. J. (2015). Uncovering patterns among latent variables: Human rights and de facto judicial Independence. Research & Politics,2(3), 1–9. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Crabtree, C., & Nelson, M. J. (2017). New evidence for a positive relationship between de facto judicial Independence and state respect for empowerment rights. International Studies Quarterly,61, 210–224. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Davenport, C. (1995). Multi-dimensional threat perception and state repression: An inquiry into why states apply negative sanctions. American Journal of Political Science,39(3), 683–713. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Davenport, C., & Armstrong II, D. A. (2004). Democracy and the violation of human rights: A statistical analysis from 1976 to 1996. American Journal of Political Science,48(3), 538–554. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dietrich, S., & Murdie, A. (2017). Human rights shaming through INGOs and foreign aid delivery. The Review of International Organizations,12(1), 95–120. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dobbin, F., Simmons, B., & Garrett, G. (2007). The global diffusion of public policies: Social construction, coercion, competition, or learning? Annual Review of Sociology,33(1), 449–472. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Donno, D., & Neureiter, M. (2018). Can human rights conditionality reduce repression? Examining the European Union’s economic agreements. The Review of International Organizations,13(3), 335–357. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dunning, T. (2004). Conditioning the effects of aid: Cold war politics, donor credibility, and democracy in Africa. International Organization,58(02), 409–423. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fariss, C. J. (2014). Respect for human rights has improved over time: Modeling the changing standard of accountability. American Political Science Review, 108(2), 297–318.

- Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R., & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The next generation of the Penn world table. American Economic Review,105(10), 3150–3182. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Findley, M. G. (2012). Bargaining and the interdependent stages of civil war resolution. Journal of Conflict Resolution,57(5), 905–932. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fox, J. (2016). Applied linear regression analysis and generalized linear models. Sage Publications, Inc. Google Scholar

- Franklin, J. C. (2009). Contentious challenges and government responses in Latin America. Political Research Quarterly,62(4), 700–714. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gandrud, C. (2015). simPH: An R package for illustrating estimates from cox proportional Hazard models including for interactive and nonlinear effects. Journal of Statistical Software,65(3), 1–20. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gartner, S. S., & Regan, P. M. (1996). Threat and repression : The non- linear relationship between government and opposition violence. Journal of Peace Research,33(3), 273–287. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gauri, V. (2011). The cost of complying with human rights treaties: The convention on the rights of the child and basic immunization. Review of International Organizations,6(1), 33–56. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gilardi, F. (2012). Transnational diffusion: Norms, ideas, and policies. In W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse, & B. Simmons (Eds.), Handbook of International Relations (Vol. 1954, pp. 453–477). Sage Publications. Google Scholar

- Gleditsch, N. P., Wallensteen, P., Eriksson, M., Sollenberg, M., & Strand, H. (2002). Armed conflict 1946–2001: A new dataset. Journal of Peace Research,39(5), 615–637. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Goodman, R., & Jinks, D. (2004). How to influence states: Socalization and international human rights law. Duke Law Journal,54(3), 621–703. Google Scholar

- Graham, B. A. T., & Tucker, J. R. (2017). The international political economy data resource. Review of International Organizations,14(1), 149–161. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2005). Trading human rights: How preferential trade agreements influence government repression. International Organization,59(3), 593–629. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2009). The power politics of regime complexity: Human rights trade conditionality in Europe. Perspectives on Politics,7(01), 33–37. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hafner-Burton, E. M., Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2015). Human rights institutions, sovereignty costs and democratization. British Journal of Political Science,45(01), 1–27. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Yiqing, Xu. (2019). How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis,27, 163–192. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Harrelson-Stephens, J., & Callaway, R. (2003). Does trade openness promote security rights in developing countries? Examining the Liberal perspective. International Interactions,29(2), 143–158. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Harrington, A. R. (2011). Don’t mind the gap: the rise of individual complaint mechanisms within international human rights treaties. Duke Journal of Comparative & International Law,22(2), 153–182. Google Scholar

- Heyns, C., & Viljoen, F. (2002). The impact of the United Nations human rights treaties on the domestic level. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. BookGoogle Scholar

- Hill, D. W., Jr. (2016). Avoiding obligation: Reservations to human rights treaties. Journal of Conflict Resolution,60(6), 1129–1158. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hollyer, J. R., & Rosendorff, B. P. (2011). Why do authoritarian regimes sign the convention against torture? Signaling, domestic politics and non-compliance. Quarterly Journal of Political Science,6(3–4), 275–327. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hoq, L. A. (2000). The women’s convention and its optional protocol: Empowering women to claim their internationally protected rights note. Columbia Human Rights Law Review,32(3), 677–726. Google Scholar

- Hugh-Jones, D., Milewicz, K., & Ward, H. (2018). Signaling by signature: The weight of international opinion and ratification of treaties by domestic veto players. Political Science Research and Methods,6(1), 15–31. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jaggers, K., & Gurr, T. R. (1995). Tracking democracy’s third wave with the polity III data. Journal of Peace Research,32(4), 469–482. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kelley, J. G., & Pevehouse, J. C. W. (2015). An opportunity cost theory of US treaty behavior. International Studies Quarterly,59(3), 531–543. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- König, T., & Finke, D. (2007). Reforming the equilibrium? Veto players and policy change in the European constitution-building process. The Review of International Organizations,2(2), 153–176. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Krommendijk, J. (2015). The domestic effectiveness of international human rights monitoring in established democracies. The case of the UN human rights treaty bodies. Review of International Organizations,10(4), 489–512. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lebovic, J. H., & Voeten, E. (2009). The cost of shame: International organizations and foreign aid in the punishing of human rights violators. Journal of Peace Research,46(1), 79–97. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Linzer, D. A., & Staton, J. K. (2015). A global measure of judicial Independence, 1948–2012. Journal of Law and Courts,3, 223–256. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lupu, Y. (2013). Best evidence: the role of information in domestic judicial enforcement of international human rights agreements. International Organization,67(03), 469–503. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lupu, Y. (2015). Legislative veto players and the effects of international human rights agreements. American Journal of Political Science,59(3), 578–594. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lupu, Y., Verdier, P.-H., & Versteeg, M. (2019). The strength of weak review: National Courts, interpretive canons, and human rights treaties. International Studies Quarterly,63(3), 507–520. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lutz, E. L., & Sikkink, K. (2000). International human rights law and practice in Latin America. International Organization,54(3), 633–659. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mansfield, E. D., Milner, H. V., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2007). Vetoing co-operation: The impact of veto players on preferential trading arrangements. British Journal of Political Science,37(03), 403–432. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- McNamara, H. M. (2019). Who Gets In? Nonstate Actor Access at International Organizations. PhD Diss., University of California, San Diego. Google Scholar

- Mills, M. (2010). Introducing survival and event history analysis. Sage. Google Scholar

- Moore, W. H. (2000). The repression of dissent: A substitution model of government coercion. Journal of Conflict Resolution,44(1), 107–127. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Moravcsik, A. (2000). The origins of human rights regimes: Democratic delegation in postwar Europe. International Organization,54(2), 217–252. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Neumayer, E. (2003). Do human rights matter in bilateral aid allocation? A quantitative analysis of 21 donor countries. Social Science Quarterly,84(3), 650–666. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Neumayer, E. (2007). Qualified ratification: Explaining reservations to international human rights treaties. The Journal of Legal Studies,36(2), 397–429. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Neumayer, E. (2013). Do governments mean business when they derogate? Human rights violations during notified states of emergency. Review of International Organizations,8(1), 1–31. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nielsen, R. A., & Simmons, B. A. (2015). Rewards for ratification: Payoffs for participating in the international human rights regime? International Studies Quarterly,59(2), 197–208. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Parente, F. (2022). Settle or litigate? Consequences of institutional design in the Inter-American system of human rights protection. Review of International Organizations,17, 39–61. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Peace Agreement between the Government of Liberia, the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy, the Movement for Democracy in Liberia and the political parties (2003). Available at https://peaceaccords.nd.edu/wp-content/accords/Liberia_CPA_2003.pdf

- Pemstein, D., Marquardt, K. L., Tzelgov, E., Wang, Y.-t., Krusell, J., & Mir, F. (2021). The V-Dem measurement model: latent variable analysis for cross-national and cross-temporal expert-coded data. V-Dem Working Paper No. 21. 2nd edition. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

- Poe, S. C., & Neal Tate, C. (1994). Repression of human rights to personal integrity in the 1980s: A global analysis. The American Political Science Review,88(4), 853–872. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Poe, S. C., Neal Tate, C., & Keith, L. C. (1999). Repression of the human right to personal integrity revisited: A global cross-National Study Covering the years 1976–1993. International Studies Quarterly,43(2), 291–313. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Powell, E. J., & Staton, J. K. (2009). Domestic judicial institutions and human rights treaty violation. International Studies Quarterly,53(1), 149–174. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schneider, C. J., & Urpelainen, J. (2013). Distributional conflict between powerful states and international treaty ratification. International Studies Quarterly,57(1), 13–27. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schoner, R. J. (2023a). Individual mobilization by victims of human rights abuse: who files complaints in the United Nations? Working Paper.

- Schoner, R. J. (2023b). Naming and Shaming by UN Treaty Bodies: Individual Petitions’ Effect on Human Rights. Working Paper.

- Shellman, S. (2006). Process matters: Conflict and cooperation in sequential government-dissident interactions. Security Studies,15(4), 563–599. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Shikhelman, V. (2019). Implementing decisions of international human rights institutions – evidence from the United Nations human rights committee. European Journal of International Law,30(3), 753–777. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Simmons, B. A. (2009a). Mobilizing for human rights: International law in domestic politics. Cambridge University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Simmons, B. A. (2009b). Should states ratify? - Process and consequences of the optional protocol to the ICESCR. Nordic Journal of Human Rights,27(1), 64–81. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Simmons, B. A., & Elkins, Z. (2004). The globalization of liberalization: Policy diffusion in the international political economy. American Political Science Review,98(1), 171–189. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Simmons, B. A., Dobbin, F., & Garrett, G. (2006). Introduction: The international diffusion of liberalism. International Organization,60(04), 781–810. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Smith-Cannoy, H. (2012). Insincere commitments: Human rights treaties, abusive states, and citizen activism. Georgetown University Press. Google Scholar

- Sokhi-Bulley, B. (2006). The optional protocol to CEDAW: First steps. Human Rights Law Review,6(1), 143–159. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sommerer, T., & Tallberg, J. (2017). Transnational access to international organizations 1950–2010: A new data set. International Studies Perspectives, 18(3), 247–266

- Spilker, G., & Böhmelt, T. (2013). The impact of preferential trade agreements on governmental repression revisited. The Review of International Organizations,8(3), 343–361. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Staton, J., Linzer, D. A., Reenock, C., & Holsinger, J. (2019). Update, A Global Measure of Judicial Independence, 1900–2015. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NFXWUO

- Tallberg, J., Sommerer, T., Squatrito, T., & Jönsson, C. (2013). The opening up of international organizations: Transnational access in global governance. Cambridge University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Tang, K.-L. (2000). The leadership role of international law in enforcing women’s rights: The optional protocol to the women’s convention. Gender & Development,8(3), 65–73. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tierney, M. J., Nielson, D. L., Hawkins, D. G., Timmons Roberts, J., Findley, M. G., Powers, R. M., Parks, B., Wilson, S. E., & Hicks, R. L. (2011). More dollars than sense: Refining our knowledge of development finance using AidData. World Development,39(11), 1891–1906. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Torfason, M. T., & Ingram, P. (2010). The global rise of democracy: A network account. American Sociological Review,75(3), 355–377. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tsebelis, G. (1999). Veto players and law production in parliamentary democracies: An empirical analysis. The American Political Science Review,93(3), 591–608. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Verdier, P.-H., & Versteeg, M. (2015). International law in National Legal Systems: An empirical investigation. American Journal of International Law,109(3), 514–533. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vilán, A. (2018). The domestic incorporation of human rights treaties. PhD Diss., University of California, Los Angeles. Google Scholar

- von Stein, J. (2018). Exploring the universe of UN human rights agreements. Journal of Conflict Resolution,62(4), 871–899. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vreeland, J. R. (2008). Political institutions and human rights: Why dictatorships enter into the United Nations convention against torture. International Organization,62(01), 65–101. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- World Bank. (2015). World Development Indicators 2015. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators/wdi-2015

- Young, J. K. (2012). Repression, dissent, and the onset of civil war. Political Research Quarterly,66(3), 516–532. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zvobgo, K., Sandholtz, W., & Mulesky, S. (2020). Reserving Rights: Explaining Human Rights Treaty Reservations. International Studies Quarterly, 64(4), 785-797.

Acknowledgements

I thank Courtenay Conrad, Christina Cottiero, Thomas Flaherty, Emilie Hafner-Burton, Stephan Haggard, David Lake, Luke Sanford, Christina Schneider, Erik Voeten, participants at the 2020 Political Economy of International Organizations Conference, the Fall 2019 Georgia Human Rights Network Workshop, the 2019 APSA Conference, the 2019 Minnesota Political Methodology Graduate Student Conference, and the IR Workshop at UC San Diego for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Political Science, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA Rachel J. Schoner